Tricky weather conditions have made it difficult for forecasters in the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season, which typically peaks in August, September and October.

An average hurricane season, which typically peaks in August, September and October, has 14 named systems, with seven hurricanes and three of them being major hurricanes.

The combination of very warm waters and a super El Niño season made 2023 predictions challenging. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which revised its forecast for the year, now predicts an above-normal season with 14 to 21 named storms (previously from 12 to 17), including six to 11 hurricanes and two to five major hurricanes.

Already, 2023 has seen more storms than anticipated, with August bringing six named storms, higher than the typical 3 to 4 storms.

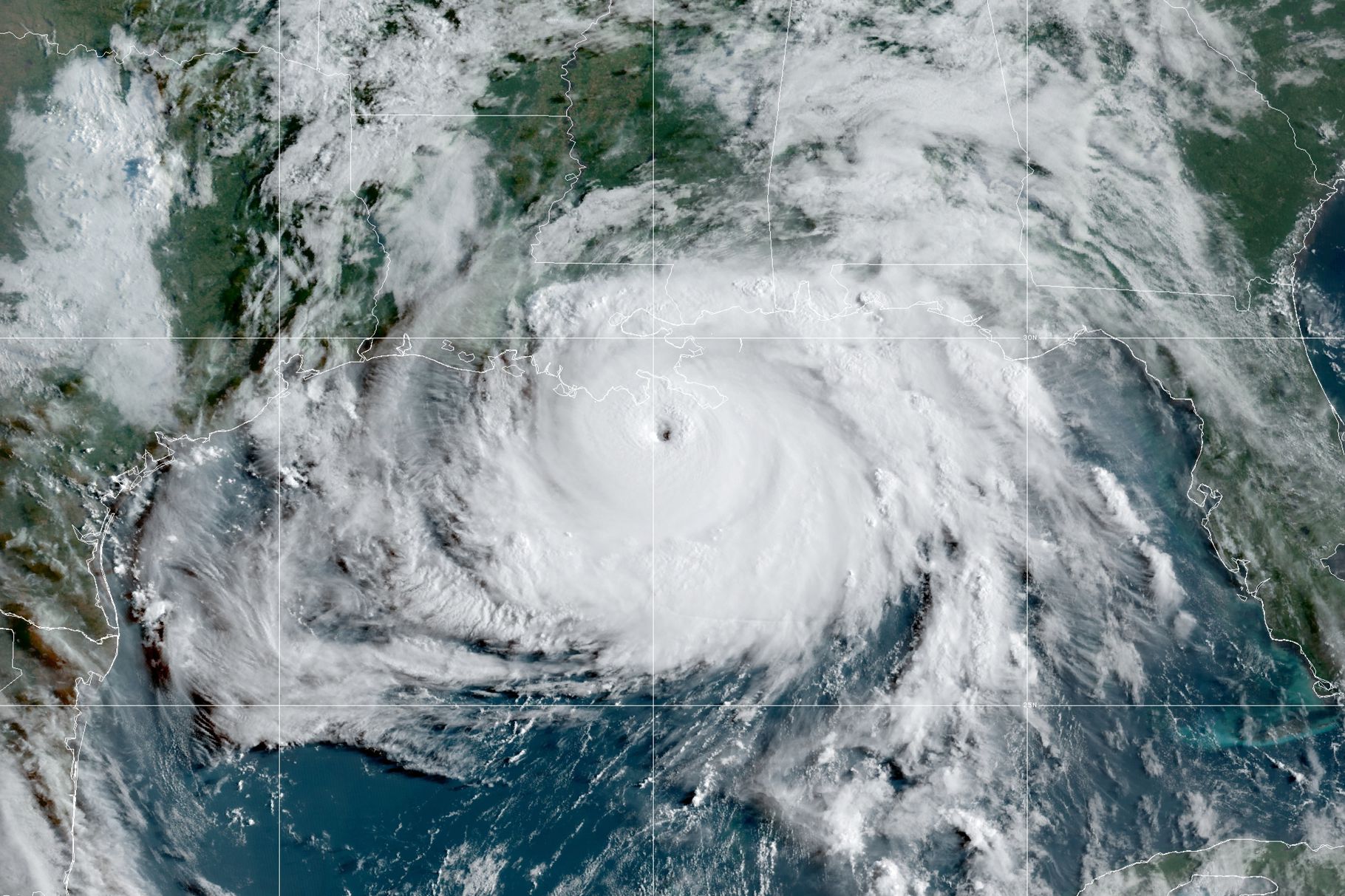

(Photo: A hurricane in the Atlantic. Source: NASA)

AccuWeather predicts 13 to 17 named storms, including four to eight hurricanes (one to three of them being major). They also predict that between two and four will directly impact the United States.

In early July, Colorado State University (CSU) released the latest update to its original predictions. The forecast team now predicts an above-average season with 18 named storms, including nine hurricanes and four major hurricanes. The 2022 season was about 75% of an average season, and CSU predicts 2023 will come in at about 130% of an average season.

The University of Arizona has not updated its June predictions, although these were an update from their original prediction and are the highest overall predictions. It is predicting a very active season with 25 named storms and 12 hurricanes, with six being major hurricanes. They say that the warm Atlantic waters will supersede the effects of El Niño.

The Weather Company’s predictions were increased in July to an above-average season with 20 named storms, ten hurricanes and five major storms.

Most storms this year are referred to as “fish storms” because they pose no risk to land. However, as noted in this news article by Nextart/WFLA, “these storms may still pose a threat to fishing boats or shipping routes, and the National Weather Service continues to issue reports on such weather systems in its High Seas Forecasts. Occasionally, ‘fish storms’ may also produce possible dangerous currents along the coasts.”

Additionally, it only takes one storm to make landfall to create significant damage, whether it is Category 1 or Category 5.

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) provides a list of the 2023 storm names.

In terms of locations, predictions said that Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands and Florida were likely to be hardest hit again in 2023, as they were in 2022. This has already proven true with Hurricane Idalia, which hit Florida at the end of August.

In 2022, there were 14 named storms, including eight hurricanes and two major hurricanes. Despite this, it also had the third costliest hurricane on record (Hurricane Ian, $114.0 billion.)

Latest Updates

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, October 23

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, September 25

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, September 18

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, Aug. 7

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, June 5

Overview

In this profile, storms in the Atlantic/Gulf regions will be listed in reverse chronological order, except for the most damaging storms, which are listed first.

Hurricane Lee

Hurricane Lee was a very long-lasting hurricane, first forming as a tropical depression on Sept. 5 in the Central Atlantic. The last advisory was issued on Sept. 17 at 11 a.m. AST, at which point Lee was a post-tropical cyclone and located about 135 miles west-northwest of Port Aux Basques, Newfoundland.

Hurricane Lee grew from Category 1 to Category 5 status in just one day on Sept. 7. Lee was the first Category 5 storm of the 2023 Atlantic Hurricane Season.

Maine saw its first hurricane watch in nearly 15 years.

Lee made landfall on Sept. 16 as a post-tropical cyclone about 135 miles west of Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia.

The storm affected a large portion of New England and Atlantic Canada with damaging winds and heavy rains that knocked down trees, flooded roadways and cut power to tens of thousands. One person was killed in Searsport, Maine, after a tree limb fell on their vehicle on U.S. Highway 1. A 15-year-old boy was killed in Fernandina Beach, Florida on Sept. 13 due to waves associated with Lee.

When Lee first made landfall in Nova Scotia at Long Beach at 4 p.m. on Sept. 16, it was considered a post-tropical cyclone but still had winds of 68 miles per hour (74 miles is the low end of a Category 1). It traveled across the edge of Nova Scotia, through the Bay of Fundy and the eye was very close to Saint John by 9 p.m. that evening with winds of about 53 mph.

Fredericton saw almost 5 inches of rain from Lee. The New Brunswick government said there was not sufficient damage for government assistance and that homeowners should contact their insurance companies. This does not address the needs of uninsured, underinsured or tenants.

Emergency management declarations were issued by President Biden for Maine and Massachusetts. All counties in both states were included in the declarations which provide Public Assistance Category B, Emergency Protective Measures. No money has been obligated for either state as of Oct. 23.

Hurricane Idalia

Idalia made landfall at Keaton Beach in Florida’s Big Bend area (wind speeds around 125 mph) as a Category 3 hurricane on Aug. 30, after briefly undergoing a rapid intensification to a Category 4 storm overnight. This area had not been hit by a strong storm in 125 years. Five storm-related deaths have been reported: one in Georgia and four in Florida. Damage assessments are still ongoing. Idalia brings the total of U.S. billion dollar weather and climate disasters to 23 as of the end of August 2023. This is the highest total, beating out the record of 22 in 2020.

Florida

Idalia made a direct landfall in Keaton Beach as a Category 3 storm on Aug. 30. The death toll and damage were significantly less than in Hurricanes Michael and Ian because the Big Bend area has a much sparser population. This rural population, however, presents challenges for recovery because fewer philanthropic and nonprofit resources are available.

Insured losses were estimated at $3 to $5 billion by Moody’s RMS. This was much lower than Hurricane Ian, which reflects the smaller population size. Unlike most counties in Florida, this area of the states has been losing residents. The state average income is $61,000 but in these communities, median income is $15,000 to $20,000, leaving 1 in 5 people living in poverty. Average home values are only around $100,000, but with the increased costs of construction materials and rebuilding, most home owners will not receive enough assistance to recover.

The storm surge was the biggest ever seen and stretched 250 miles (from Mexico Beach, hit by Michael in 2018, down to Naples, which Ian hit in 2022). In a preliminary report released Sept. 18, the National Weather Service found that the storm surge reached 12 feet above dry ground.

In the area of landfall near Keaton Beach, water levels between 7-12 feet higher along more than 33 miles of coast to the north and south of the center. Steinhatchee and Cedar Key, in the Big Bend area, had 10 feet of storm surge, and even Tampa Bay, 150 miles south, saw four feet of surge. The Sun Sentinel reported: “It was the largest surge Tampa had seen since the 1921, when, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Tampa Bay/Tarpon Springs Hurricane brought 11 feet of storm surge to the city.”

Many islands and peninsulas were cut off from the mainland for hours as extensive flooding was experienced in many barrier islands as far south as Pinellas County. The barrier islands lost several years of dune recovery.

According to Axios, “Ping Wang, a professor in the School of Geosciences who has studied west Florida beach erosion for 20 years, told the Tampa Bay Times it was the worst erosion he’d ever seen from a single storm.”

Thousands of people experienced damage from winds, rain and flooding.

A federal disaster declaration (DR-4734) was approved for most counties in Florida. Individual assistance is provided in 16 counties. Public assistance of some kind was approved for all but 18 counties. As of Oct. 23, 34,287 individual assistance applications had been approved for a total commitment of $71.17 million. For public assistance categories A and B, almost $274 million has been obligated.

Georgia

The Georgia coast was not as hard hit, but the more rural communities in south-central Georgia were strongly affected.

The most affected area was the Valdosta area, which saw flooding and downed trees and power lines blocking streets. The Valdosta Daily Times reported that Lowndes County (where Valdosta is located) had insured losses of about $12.8 million.

Also, on Sept. 6, Governor Brian Kemp officially requested a federal disaster declaration for 30 counties for public assistance and four counties for individual assistance. The governor estimated that the total cost of public assistance needs was over $41 million. Kemp said, “… the specific counties hit by Hurricane Idalia have significant vulnerable populations. Any instability is potentially catastrophic to the health and wellbeing of these communities.”

President Biden approved the governor’s request for a major disaster declaration (DR-4738) on Sept. 7, and as of Oct. 23 1,150 applications for Individual Assistance (IA) had been approved for five counties for a total obligation of $3.51 million. There were 29 counties approved for Public Assistance, A to G, and no funds have been obligated.

South Carolina

Idalia moved through South Carolina overnight on Aug. 30 as a Tropical Storm. Compared to Florida and Georgia, there was only minimal damage. Water at Charleston Harbor exceeded 9 feet, the fifth-highest water level ever recorded.

President Biden approved an emergency management declaration in South Carolina (EM-3597) on Aug. 31 for 23 counties to receive Public Assistance, Category B, emergency protective measures. This does not provide any assistance for individuals. No funding obligations have been announced as of Oct. 23.

North Carolina

Idalia moved into North Carolina as a tropical storm. As it crossed the state, the biggest impact was from I95 to the coast, where about 7 inches of rain fell. This led to minor street flooding. There were also six confirmed low-level tornadoes, which caused minimal damage. Idalia left the state at tropical storm strength before eventually dissipating at sea.

Hurricane Franklin

On Sept. 1, Franklin became an “extratropical” cyclone, which Science Direct defines as “a storm system characterized by a low-pressure and cold-core centre with weather fronts that can produce thunderstorms and heavy precipitation.” Franklin passed Bermuda as a Category 2, and only the storm’s outer bands affected the island. Given the distance, Franklin’s winds were more similar to a tropical storm than a hurricane.

A long-lasting storm, Franklin made landfall on Hispaniola on August 23, bringing flooding and fears of mudslides to the island. Rain in Santo Domingo exceeded 1.1 feet. In the Dominican Republic, at least 670 homes were damaged by the storm. Two people were killed and one other was reported missing. More than 1.6 million people were left without water.

Other storms

- Hurricane Tammy: The first advisory was issued on Oct. 18, when Tammy was a tropical storm located 625 miles east of the Windward Islands. It became a hurricane on Oct. 20 with winds of 75 miles an hour, when it was 90 miles northeast of Barbados. As of 11 a.m. Atlantic on Oct. 23, Tammy was still a Category 1 hurricane with wind speeds of 80 mph. It was located 260 miles north of Anguilla. There is some rain and storm surge risk in the U.S. and British Virgin Islands, the Leeward Islands and Puerto Rico over the next few days, but is otherwise a fish storm.

- Tropical Storm Sean: Sean formed as a tropical depression on Oct. 10 in the eastern Tropical Atlantic, 690 miles southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. By early on Oct. 11 (5:00 a.m. Atlantic) it was a tropical storm, but was not expected to strengthen much. Sean remained a fish storm and dissipated as a remnant low on Oct. 15, 905 miles east of the Northern Leeward Islands.

- Tropical Storm Rina: On Sept. 28, Tropical Storm Rina formed over the Central Tropical Atlantic. Rina stayed over that area and dissipated on Oct. 1.

- Tropical Storm Philippe: Tropical Storm Philippe formed as a tropical depression on Sept. 23 and became a tropical storm a few hours later. Philippe made one landfall in Barbuda on Oct. 2. It became a post-tropical cyclone on Oct. 6 when it was located about 110 miles south of Bermuda. It hit the island with strong winds and rain but did not cause extensive damage. Philippe then traveled on to New England and Atlantic Canada, although rainfall was less than anticipated. Overall, damages were minimal.

- Hurricane Nigel: Nigel formed in the central Atlantic as a Tropical Depression on Sept. 15, before becoming a Tropical Storm on Sept. 16 and a hurricane on Sept. 18. Nigel became extratropical on Sept. 22 about 640 miles north-northwest of the Azores.

- Hurricane Margot: This storm formed as a Tropical Depression on Sept. 7 before becoming a Tropical Storm the same day. On Sept. 11, Margot became the fifth hurricane of the 2023 Atlantic Hurricane Season. It reached only a Category 1 status and remained in the Atlantic Ocean. Margot was a fish storm and lost tropical cyclone status on Sept. 17.

- Tropical Storm Jose: Jose was absorbed into Hurricane Franklin on Sept. 1.

- Tropical Storm Harold: Although Harold developed into a Tropical Storm with winds of 50 mph, its impact was not as severe as anticipated. It made landfall on Padre Island in South Texas on Aug. 22 at 10 a.m. CDT. It was the first U.S. landfall of the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season. Harold quickly weakened into a tropical depression as it made its way through Texas. Although there was some minor flooding, the biggest impact was a widespread but short-lived power outage.

- Tropical Storm Gert: Gert was a short-lived tropical storm. It became a tropical storm on Monday, Sept. 4, and dissipated later the same day.

- Tropical Storm Emily: A very short-lived tropical storm, Emily formed on Aug. 20 and, by the next day, had already become sub-tropical. Emily was a fish storm, traveling west-northwest through the Atlantic Ocean.

- Hurricane Don: Don formed as a sub-tropical storm over the central Atlantic on July 14. Don became the first named hurricane of the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season on July 22. Don arrived a few weeks early compared to normal, as the first named hurricane does not usually form until August 11. Don was a quick and mild hurricane with no impact on land. By July 23, it had already been downgraded to a Tropical Storm and dissipated on July 25 over the North Atlantic.

- Tropical Storm Cindy: Tropical Storm Cindy formed in the evening of June 22. It was one of two systems to emerge in the same week from the Main Development Zone, a very unusual occurrence this early in the season. Cindy was the third named storm of the season, something that, on average (1991-2020), does not occur until Aug. 3.

- Tropical Storm Bret: Tropical Storm Bret formed on June 19 from a wave that moved off the African coast on June 15. It crossed the Lesser Antilles and then entered the Caribbean Sea. As with Tropical Storm Cindy, this early formation in the Main Development Zone is unusual. On June 22, Bret came close to becoming the first named hurricane of the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season, but wind shear prevented further development, keeping it a tropical storm.

- Tropical Storm Arlene: Tropical Storm Arlene became the first named storm of the season on Friday, June 2, just one day into hurricane season. Arlene brought some heavy rain to Florida, but otherwise had minimal impact before dissipating on June 4. It can be considered a fish storm.

- Invest 90L/AL012023: The rare January disturbance in 2023 formed in mid-January and brought cold weather and snow to the Atlantic northeast. Originally, it was believed that it did not reach subtropical status, but it was reclassified on May 11 as the first storm of the season.

Housing

Many people struggle to find safe and affordable housing following a hurricane, particularly those from poor and marginalized backgrounds. For example, in 2021, Hurricane Ida exacerbated an affordable housing crisis in New Orleans as housing supply post-disaster was low, but demand was high. This was also true after Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico and Hurricane Ian in Florida in 2022.

The amount of work needed and ability to recover depends on the amount of damage. Houses that are only partially damaged may only need to have mucking and clean-up, debris removal, and tarping of roofs. Houses that experienced flooding will have to be gutted at least to three feet on the inside and undergo mold remediation.

Housing prices in southern Florida increased significantly after Hurricanes Ian and Nicole in 2022, limiting the ability of renters and people living in poverty to find housing. Florida was already experiencing a housing crunch before the hurricanes, which has made recovery harder for people already struggling to make ends meet.

Renters are often subjected to unfair evictions after disasters, as landlords realize they can increase rents due to the shortages. Wealthier homeowners likely have insurance that will also allow them to rent temporary housing during repairs, further restricting the rental market. However, numerous insurance companies have closed in Louisiana and Florida. Finding new insurance after a storm may be even more difficult and prices are higher.

Linked to this is the need for income support programs. Many damaged homes in recent years were among low and middle-income residents and/or retirees on fixed incomes. They do not have the resources to rebuild their homes themselves, or the ability to recover generally from a disaster. FEMA assistance and insurance are often insufficient to meet needs, so additional funding is required to help cover the costs of repairs and rebuilding.

Mobile and manufactured housing

While housing, in general, is always a significant need, the crisis is worse for those who are living in manufactured or mobile homes.

The standards for manufactured homes changed after Hurricane Andrew in 1992 because of the significant impact that storm had on mobile homes.

The revised 1994 standards for mobile homes increased safety and ability to withstand hurricane-force winds for residents. In Punta Gorda, Florida, the homes were all built to post-1994 standards because they were destroyed during 2004’s Hurricane Charley. As a result, 99% of the homes made it through Hurricane Ian, with only minimal siding, skirting or roof damage.

CDP hosted a webinar on Oct. 13, 2022, on mobile housing during disasters, which offers advice for funders on supporting these communities. CDP has a new toolkit with advice for recovery in manufactured housing communities.

Economic losses and community development

The compounding effects of COVID-19 delayed recovery after storms from 2020 to 2022. Livelihood support and investment in local economies are still needed for people to recover fully.

Extensive power outages often follow hurricanes, increasing costs for individuals and businesses alike.

The location of a storm can also influence the ability of a community to recover. For example, Florida and Puerto Rico are popular tourist destinations, and the storms in 2022 significantly impacted future revenue.

One organization measures the impact of lost revenue and expenditures in a disaster-affected area. The Perryman Group says that the net impact of Hurricane Idalia could include economic losses for the United States of “$42.2 billion in total expenditures and $18.4 billion in gross product, with about $34.4 billion in total expenditures and $15.0 billion in gross product in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.”

There could also be a loss in the four states of almost $10 billion ($12.1 across the U.S.) in personal income, including wages and rental income. The increase in construction activity, and the need to replace lost items such as clothes, appliances, furniture and vehicles, will offset some of the losses.

Agricultural and fisheries

In Florida, there was a significant impact on the fishing industry in the Big Bend area. This included loss of boats and docks, loss of product during power outages, and inability of commercial and charter fishing boats to work.

According to the Florida Emergency Management Department, “Florida leads the nation in the number of saltwater fishing anglers, generating a $9.2 billion impact on the State of Florida’s economy. Additionally, the dockside value of commercial fisheries is estimated at $244 million. The financial assistance from this disaster declaration would help replace fishermen’s lost income and rebuild their businesses and infrastructure.”

In Georgia, there was significant agricultural damage.

Morning AgClips, a leading agricultural news service, said: “Initial assessment reports released by the Georgia Department of Agriculture and UGA Extension detailed major agriculture damage in [13 counties] … Idalia uprooted pecan trees, blew over corn and cotton stalks, battered vegetable plants, and tossed tobacco leaves to the ground. She also damaged farm equipment, sheds and fences. Numerous farmers had to run generators to keep their dairy and swine barns, poultry houses, tobacco curing barns and wells operating for days until power was restored.”

This included (as cited in Morning AgClips):

- Pecan farmers were hard hit in several counties as harvest was only a month away. It is estimated that 10,000 to 15,000 trees were downed from large growers’ orchards; this doesn’t include the losses for small farmers. Depending upon the orchard this could be anywhere from 30-80% of trees and 50% to 80% of crop loss. Most of the trees that fell were mature trees, over 20 years old, so the damages include lost future production. Younger trees were able to bend more with the wind, but there were still losses from tree limbs breaking or unripened nuts falling.

- Many poultry farmers were affected because of the loss of power after the hurricane. Livestock perished after cooling systems couldn’t function.

- Tobacco farmers were in the third stage of the harvest, which includes removing leftover leaves from stalks. Ability to proceed after Idalia depended on the exact stage the farmer was at and the condition of the soil. Additionally, most farmers were curing their recently harvested tobacco which requires fans. Loss of power meant a reliance on generators.

Donors and funders can support funds set up to help these populations, e.g., through state Farm Bureaus. They can also work with local community foundations or other funders to provide resources to community groups supporting economic development and livelihood recovery.

Health and behavioral health

Research shows that hurricanes cause and exacerbate multiple diseases. While many health impacts peak within six months following hurricanes, chronic diseases continue to occur for years.

Hurricanes also inflict harm to the mental health of people in their paths. According to research from Vibrant Emotional Health, the repeated stress of chronic cyclical disasters causes trauma in ways that are not fully understood. This research is key to helping mental health professionals fully understand the needs of survivors.

Donors should look into long-term investment in mental health support. Government-funded or NGO-led emotional and spiritual care programs tend to be short-term, but research has shown that long-term support is required.

Funders could ensure that therapy programs are offered for all ages, are conducted in community settings and exhibit high levels of cultural competency to meet the diverse needs of clients by providing funds for local organizations embedded in hyper-local networks and communities.

Navigating assistance processes

Disaster assistance may be available in various forms and from different sources. People will need help navigating a complicated assistance process, particularly undocumented people and people whose first language is not English.

A recently released study from the U.S. Commission on Human Rights found that FEMA did not equitably serve at-risk populations, including people with disabilities, people living in poverty and English as a second language speakers, during Hurricanes Harvey or Maria in 2017.

CDP grantee SBP USA (formerly St. Bernard Project) provides support for FEMA appeals. This includes online resources and videos for survivors, as well as training for NGO staff and in-person support when needed. Supporting programs such as this is a great investment for donors.

Government recovery assistance

Infrastructure spending is always an important area and challenge for communities. While the federal government provides support in recovery for U.S.-based disasters, there is usually still a 25% cost-share that some local governments may have issues affording. Funders could pay the 25% for small communities or support the back-end and technical assistance needs of applying for a government grant.

FEMA assistance is not enough for most survivors. Research from the federal Government Accountability Office (GAO) “found that fewer than half of the applicants for relief under FEMA’s Individual and Housing Assistance program between 2016 and 2018 — most of whom were uninsured or had an income under $50,000 — qualified for aid. For those who do qualify, the FEMA funds can be inadequate to cover the cost of rebuilding. Payments max out at $36,000 for home-rebuilding assistance and the average payout from FEMA is just $8,000.” Even this is an increase from a 2020 GAO report that found, “On average, FEMA awarded about $4,200 to homeowners and $1,700 to renters during 2016 through 2018.”

Other countries may not have the structural funding programs that the U.S. has in place. Philanthropy can help by supporting infrastructure. For example, funders could provide support for communities to purchase equipment, buildings, vehicles or training for first responders.

The CDP Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund is a permanent fund, allowing CDP the most flexibility to respond to philanthropic and humanitarian needs as they arise. You can donate to the fund to support hurricane recovery.

Contact CDP

Philanthropic contributions

If you would like to make a gift to the CDP Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund, please contact development.

(Photo: Hurricane Ida over the Gulf of Mexico approaching Louisiana. Source: GOES-East NOAA)

Recovery updates

If you are a responding NGO or a donor, please send updates on how you are working on recovery from this disaster to Tanya Gulliver-Garcia.

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Donor recommendations

If you are a donor looking for recommendations on how to help with disaster recovery, please email Regine A. Webster.

More ways to help

As with most disasters, disaster experts recommend cash donations, which enable on-the-ground agencies to direct funds to the greatest area of need, support economic recovery and ensure donation management does not detract from disaster recovery needs.

CDP has also created a list of suggestions for foundations to consider related to disaster giving. These include:

- Take the long view: Even while focusing on immediate needs, remember that it will take some time for the full range of needs to emerge. Be patient in planning for disaster funding. Recovery will take a long time, and funding will be needed throughout.

- Recognize there are places private philanthropy can help that government agencies might not: Private funders have opportunities to develop innovative solutions to help prevent or mitigate future disasters that the government cannot execute.

- All funders are disaster philanthropists: Even if your organization does not work in a particular geographic area or fund immediate relief efforts, you can look for ways to tie disaster funding into your existing mission. If you focus on education, health, children or vulnerable populations, disasters present prime opportunities for funding.

- Ask the experts: If you are considering supporting an organization that is positioned to work in an affected area, do some research. CDP and National VOAD (U.S.) and InterAction (international) can provide resources and guidance about organizations working in affected communities.

Philanthropic and government support

The Center for Disaster Philanthropy’s Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund is a permanent fund that focuses on the full spectrum of the disaster cycle. The following are examples of grants awarded through this fund:

- CDP awarded a $250,000 grant to United Policyholders to deliver recovery assistance services to households impacted by Hurricanes Ian and Nicole through the time-tested Roadmap to Recovery(R) (“R2R”) and Advocacy and Action programs. This includes continued communications initiated with insurance industry representatives, attorneys and claim adjusters aimed at setting new ground rules for the appraisal process.

- CDP awarded a $200,000 grant to the Hope DeSoto Long-Term Recovery Committee to increase long-term recovery efforts in DeSoto County, Florida and to build resiliency in the community.

- CDP provided a $500,000 grant to for SBP USA and its partners can return at least 22 vulnerable, Hurricane Ian-impacted families to the safety and security of their homes. SBP’s long-term recovery work will not only lay the groundwork for continued recovery efforts throughout the region, but will also position local nonprofits to leverage additional resources to drive community resilience initiatives for years to come.

- CDP awarded a $450,000 grant to Equal Justice Works to enhance the capacity of its Disaster Resilience Program to deliver legal services by mobilizing legal fellows to partner organizations in Florida and Puerto Rico to serve low-income communities impacted by Hurricanes Ian and Fiona and at risk of future disaster. Fellows will provide direct legal services; conduct education and outreach; conduct policy and systems change work; and train pro bono and other legal aid attorneys to promote disaster preparedness, recovery and long-term resilience.

- CDP provided Fundación de Mujeres en Puerto Rico with a $250,000 grant to support the grass-roots, women-led organizations that possess the deepest expertise regarding what disaster-recovery assistance is needed in Puerto Rico’s most vulnerable communities—and that are invariably the first boots-on-the-ground offering that assistance. The grant will provide the holistic operational, strategic and emergency resources that organizations need to continue carrying out their life-saving work with maximum effectiveness.

Resources

Hurricanes, Typhoons and Cyclones

Hurricanes, also called typhoons or cyclones, bring a triple threat: high winds, floods and possible tornadoes. But there’s another “triple” in play: they’re getting stronger, affecting larger stretches of coastline and more Americans are moving into hurricane-prone areas.

Insurance

Each natural disaster reminds us of the value of insurance to protect our homes and businesses. But with the news filled with stories about homeowners still waiting to settle claims, or insurance covering less damage than expected, what is the role of private insurance in disaster recovery?

Crisis Communications

When a disaster strikes, a crisis communications plan that uses the six pillars of crisis communications will allow staff to communicate clearly, concisely and in ways that match your organization’s and community’s needs.